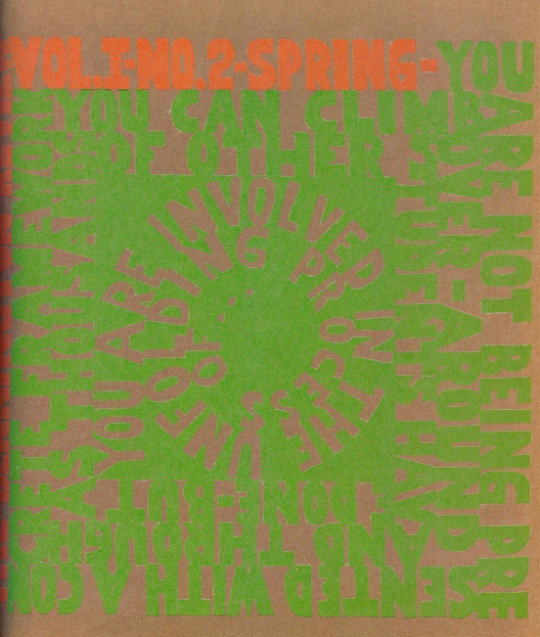

A Bennington Review cover from 1967. The text reads, in part, “You are not being presented with a concrete framework you can climb over–around and through …”

Of all the forms of literary culture that weren’t supposed to survive the Internet, the print journal has proved to be remarkably adaptable—and feisty. N+1 and A Public Space spawned a generation of literary startups, and venerable journals like The Paris Review are attracting more subscribers than ever before.

This year, poet and literature faculty member Michael Dumanis has taken it upon himself to revive Bennington Review, a magazine that was originally founded in 1966 by Laurence J. Hyman (see our interview with Hyman about his history with the journal). Dedicated at first to showcasing work by Bennington faculty and alumni, Bennington Review gradually opened its pages to artists and writers outside the College community. Then the money ran out and it closed up shop.

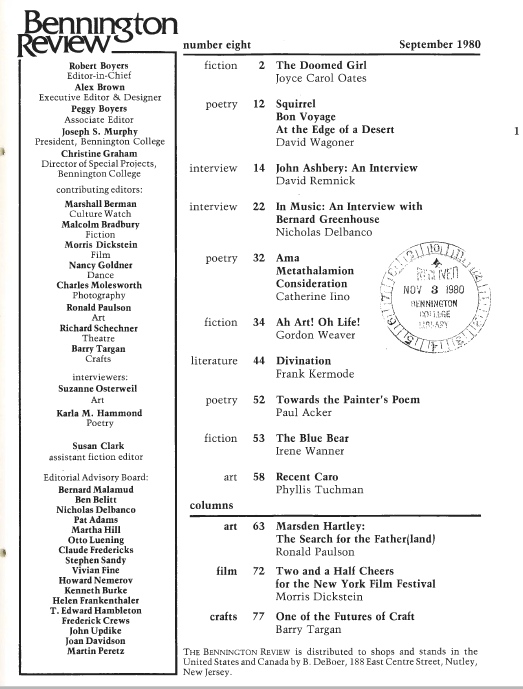

In 1978, Bennington Review was relaunched under the direction of Robert Boyers and Nicholas Delbanco; this new iteration of the journal attracted a group of intellectual heavyweights (Marshall Berman and Morris Dickstein were both contributing editors) and published work by some of the biggest literary names of the day, including John Updike and Joyce Carol Oates.

After a thirty-year hiatus, the first issue of the new Bennington Review will be published in March 2016. We asked Dumanis a few questions about why he decided to bring back this influential journal now and what his plans are for breathing new life into the literary magazine.

Literary Bennington: What inspired you to revive Bennington Review? Why now?

Michael Dumanis: I remember the first time I read a literary journal, a long-defunct thing called Caliban and another long-gone magazine called Sulfur, both of which I stumbled upon as an undergrad in the mid-nineties in my college’s library. In my poetry workshop that term, we read full-length collections that were all perfectly fine and ultimately fairly similar. My notion at age 20 of what was happening in American poetry, of what was possible to do in the space of a page, was limited. Those issues of Caliban and Sulfur exposed me to a kind of work that stretched my paradigm of what a poem could be.

Around the same time, I remember encountering in a Kenyon Review someone had left lying around a short story by a guy named Gerald Shapiro about a sad- sack widower named Levidow who was convinced by God to go on a cross-country roadtrip in a big blue car with a reincarnation of himself as a younger man and an absurd quantity of Dr. Brown’s sodas. It was such a weird, wild story, so much more alive as a piece of writing than most things I was reading for school. So basically, that’s how I came to fall in love with literary magazines.

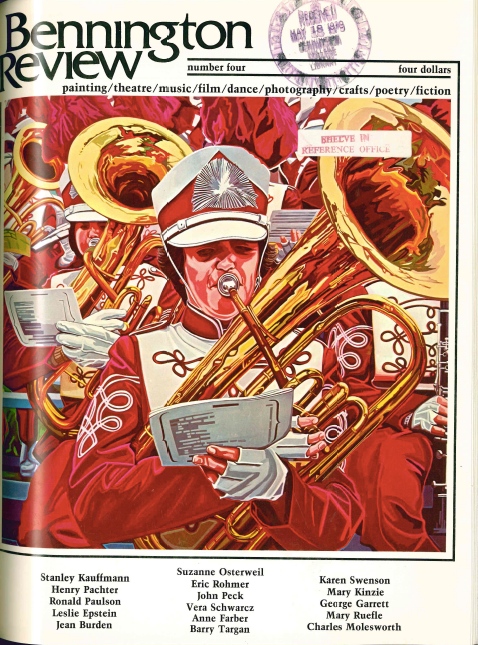

A cover of Bennington Review from 1979

Since then, I have had a lot of opportunities to be an editor. As a PhD student, I was poetry editor of the journal Gulf Coast for four issues: I found it thrilling to read such a diversity of work from around the world and to collaboratively make difficult, meaningful choices about which pieces to bring together. I went on to coedit, with the poet Cate Marvin, Legitimate Dangers: American Poets of the New Century, a mammoth anthology of 85 emerging poets. With Kevin Prufer, I coedited a book of poems by, and criticism about Russell Atkins, a relatively obscure and quite brilliant African-American poet of the ‘60s and ‘70s. And before coming to Bennington, I spent five years as the Director of the Cleveland State University Poetry Center, which has been publishing books of poetry for forty years but had fallen off the radar as a publisher; I helped revitalize the press as a home for innovative emerging poets who were attempting truly exceptional feats of language and line in their manuscripts.

In short, I’ve always been drawn to editing—to discovering, highlighting, and bringing together truly exceptional pieces of writing by a variety of voices, that when juxtaposed alongside one another, communicate more powerfully and in a different way than they would individually.

When I came to Bennington, I was aware that the college once had a notable literary magazine. The old issues are amazing—snapshots of some of the more exciting and engaging work being produced in their particular time. Each issue was an event. Poring over the old magazines, I made a lot of real discoveries, like a terrific interview of John Ashbery that now-New Yorker editor David Remnick conducted as a Princeton grad student 35 years ago.

I look forward to reviving this high-caliber publication at Bennington, while giving undergraduate students hands-on experience staffing a faculty-edited print journal. I also want to make an argument for the lasting value of print literary magazines in a 21st century digital culture where online publications are inherently more visible and accessible.

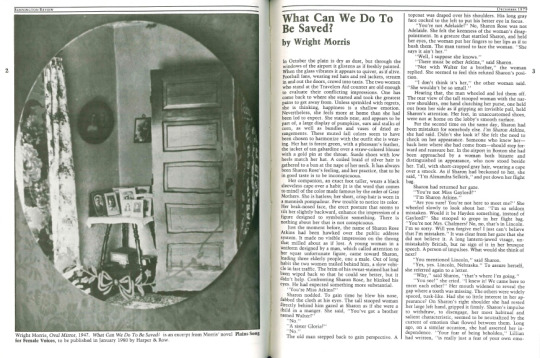

Artwork and fiction from Wright Morris in an issue of Bennington Review from 1979

LB: This will be the third iteration of the journal. What will be different? What will stay the same? What are you trying to preserve?

MD: What will stay the same: The old Bennington Review published exciting, vital, aesthetically distinctive work. We’re very proud of that legacy, and intend to build on it. On the website, and perhaps in the print issue itself, we intend to feature time capsules of some of the more fascinating excerpts from the original magazine.

What will be different: Well, for one thing, it’s going to look different. The old magazine had the dimensions of a newsstand periodical—like a magazine you would read on a plane. It aimed to capture Bennington’s interdisciplinarity by having work in a wide range of genres, from art history to dance criticism to fiction and poetry to visual art. The new Bennington Review will focus squarely on contemporary fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction, with occasional film writing and interviews.

Aside from cover art—our first will be a photograph by the artist Simen Johan—we don’t presently plan to include art in the magazine. The dimensions of the journal will be more in keeping with contemporary litmags like Tin House and Fence: shorter and more squat, with wide margins and generous page counts. Ideally, we hope for each issue to feel like a particular artifact, a space to enter and lose oneself.

Bennington Review’s masthead from 1980, when the magazine was edited by Robert Boyers

LB: What does the editorial team look for in submissions? Is there a specific voice/image you’re trying to cultivate?

MD: We consciously seek work that is at once innovative, intelligent, and moving. We like writing that is playful but also relentless, writing that is willing to takes risks in form and content in order to make lasting intellectual and emotional connections with a reader. We’re interested in startling, unexpected work from an aesthetically broad and culturally rich spectrum of writers. We’re hoping to create a publication that feels inclusive and wide-ranging while remaining distinctive in style and substance.

Some of the many newer literary journals we admire in terms of their aesthetic and format, which we think are at the forefront of a revitalized print litmag subculture, include A Public Space, Bat City Review, Black Clock, The Common, Copper Nickel, Ecotone, Freeman’s, jubilat, Lana Turner, Noon, and The Normal School. We were also really impressed by Uzoamaka Maduka’s ambitious American Reader venture, and are very sorry to hear that the magazine is closing.

Online publications toward which we feel particular aesthetic kinship include BOAAT, Catapult, Memorious, Octopus, The Offing, The Paris-American, Prelude, The Volta, and the Academy of American Poets’ Poem-A-Day series.

LB: Pretty much every university and liberal arts college in the country has its own literary journal. What makes Bennington Review unique? What about Bennington as a college makes it prime to house a project like this?

MD: It’s the contents of a journal that make it something you ultimately want to spend time with. Based on the work we have accepted thus far, I believe we’re making something particular and pretty interesting. Contributors to the first issue include, among quite a few others, Rae Armantrout, Rick Barot, April Bernard, Erica Bernheim, Jericho Brown, Cynthia Cruz, Christopher DeWeese, Carolina Ebeid, Jessica Fisher, Laura Kasischke, Porochista Khakpour, Noelle Kocot, Dorothea Lasky, Dana Levin, David Stuart MacLean, Dora Malech, Sabrina Orah Mark, Michael Martone, Joseph Massey, Ted Mathys, Shane McCrae, Reginald McKnight, Lo Kwa Mei-en, Josip Novakovich, Hai-Dang Phan, David James Poissant, Robyn Schiff, Sandra Simonds, Safiya Sinclair, Monica Sok, J.M. Tyree, G.C. Waldrep, and Wendy Xu.

Why at Bennington? When I told a very sleepy-looking Associate Dean at my last job that I was offered a position at Bennington College, he contemplated me for a moment, shrugged, and said, “Bennington? That’s jazzy.” The administration here is committed in an extraordinary, genuine way one rarely sees anymore to the nurturing and encouragement of exciting new projects in art, music, theater, dance, and literature. We’d like to do our part to join the conversation.

LB: On the Tumblr page you’re using while the website is being constructed, the tagline is “birds, not birdcages.” What exactly does that mean? Is it a reference to something?

MD: It’s a quote from the poet Dean Young’s booklength meditation on writing poetry, The Art of Recklessness. He expresses a frustration with the idea that the most important thing in writing poetry is a mastery over craft. He writes, in all caps and with more than a little exasperation, “WE ARE MAKING BIRDS, NOT BIRDCAGES!”

What is a bird, ultimately, but a perfect synthesis of recklessness and grace?